In their shiny new e-commerce avatar, can battered AA rebrand, be forgiven by justice-minded Millennials, and embraced by woke Gen Zers?

For Sam, Tuesdays meant one thing – the conference call. For one hour each week, every American Apparel store manager, visual merchandiser, and back-stock director the world over dialed into stream-of-consciousness rants from then-CEO Dov Charney, each employee praying they weren’t the unlucky soul singled out for reprimand.

During his three years working at AA stores in Seattle, Sam, a sales associate turned visual merchandiser, became accustomed to what he describes as the company head’s “Trump-esque” tirades. Some store manager in Ann Arbor would be called out for slow sales, or a back-stock director in Tel Aviv would be given a raise for suggesting a new sock color. It was that arbitrary and unpredictable. Sam didn’t love the work, but he wanted to be part of such a cool brand.

Back then, there was a certain prestige in being connected with the hyper-sexual, made-in-America label. The clothes were cool and ethically made, the aesthetic was very “in”, and anyone who worked there was “in” by extension. But, while AA had all the right optics, the reality of working there was not in line with its image.

Looking back, Sam says his hours were routinely taken away as punishment for “infractions”, and understaffing put unnecessary pressure on store managers who were “mainly a bunch of 19 and 20-year-old kids trying to figure it out on the fly.”

AA filed for Chapter 11 in November, 2016, with $234.9 million in debts, a steep descent from its peak profitability of $634 million in 2013. Bad news for hipsters now required to seek a new neon bodysuit supplier, but comeuppance for employees who came to see the oversexualized, super skinny, white AF label as all that’s wrong with the fashion world.

When Sam heard that his former employer was back, this time online-only, he couldn’t help shaking his head. “Honestly, I thought it was foolish. They just aren’t relevant anymore. There are other brands doing the same thing with less bad press.”

All the same, and for better or worse, AA is back. The new site, launched last August in the US and globally just this April, features a “back to basics” campaign, complete with iconic neon bodysuits, crop tops, hoodies, and all the rest. The difference between American Apparel then and American Apparel now seems to be, essentially, the absence of brick-and-mortar sales points, and a tacked-on mantra-du-jour of “diversity and inclusiveness”. The April press release stated new AA models would be “real people who represent a diversity of body types, ages and ethnicities.”

But can our memories really be that short? Could AA truly now be all #goodvibesonly, or are someone’s shiny disco pants on fire? The challenge in courting of Millennials and Gen Zers will be proving authenticity in a political climate that demands corporate integrity in exchange for brand loyalty.

Sarah Wilson, Head of People at SmartRecruiters, and former director of talent acquisition for Aritzia, has no illusions about what AA is up against in their search for redemption in this day and age. “It’s a really competitive industry to begin with, but rebranding now, on the heels of movements like #timesup and #metoo, will be an uphill battle, more so than it would have been five years ago, or will be five years from now.”

This challenge is even more pronounced for a brand whose ad campaigns cashed in on the sexy-skirting-pervy vibe, ever since its first store opened in LA in 2003. The AA aesthetic, often described as “porntastic” and previously lauded as edgy, crossed into creepy once its founder and CEO, Dov Charney, admitted to masturbating in front of a female reporter from Jane. This opened the doors for a slew of complaints from employees claiming sexual harassment, all of which ended in a $3M payout from the company, and $9.3M in legal fees.

AA’s current head of brand marketing, Sabina Weber, claimed in a recent interview with Fashionista that “the brand is still sexy, but it’s about a woman’s choice to be sexy; it’s in the gaze; it’s ‘If I wanna show my ass to the world, I’m gonna show my ass to the world’.”

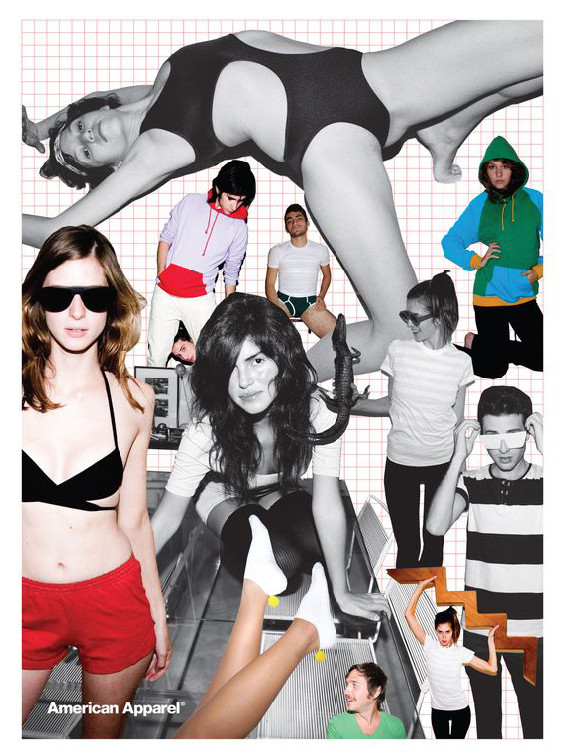

The first picture is a swimsuit campaign from the brand’s latest iteration, while the “Spring Fever” addition is taken from the AA archives. The difference is negligible, even if, under the wing of their Canadian acquirer, Gildan Activewear, the company raised the minimum age of models to 21, and in their most recent casting call requested they be over 25.

It could be argued, however, that anyone over 25 remembers AA scandals like the “teens do it better” t-shirt – created in collaboration with Ey! Magateen, a magazine “celebrating the sexuality of young men”, which used models as young as 16. AA also owned the maxim “all press is good press” by notoriously having ads banned for sexualizing school-age girls.

Other efforts of the new dispensation include employing more female photographers, and sourcing brand ambassadors from social media – the people they refer to as “real models” – and staffing AA HQ with roughly 25 mostly young, mostly female employees. (In its heyday the label employed 10,000 people.)

So what more can AA do to let consumers and candidates know it’s taking this second chance seriously? For Joel Cheesman, employer branding expert and founder of Ratedly – an employer reputation management platform – it’s simple: “People are willing to forgive when you admit wrongdoing and outline the ways change will occur.”

If you ever find yourself in AA’s situation, Cheesman suggests ridding yourself of anyone in a leadership position from the past, particularly the CEO, bring in people with a flawless background to lead the company, and spin how tomorrow is “a new day and a fresh start” to the media.

American Apparel may be off to a good start in re-establishing themselves as socially conscious, but even with the figurehead gone – and running a copycat company called LA Apparel – have the hiring practices he created really been eradicated, and if so, what else needs to change for AA to claim a true transformation?

As Dov Charney has said in the past, “I am in the DNA of the company,” and it’s true, but his imprint is pathological. The dysfunction is in the proverbial company fabric, and it’s going to be hard to get the Dov stank off these ethically made clothes.

To wit, the following email that internal AA investigators, keen on finding evidence to oust the troublesome CEO, found addressed to Charney from a female employee:

Add this to other accounts of Charney yelling racial slurs, sending pornographic emails to employees, then later, during the investigation, requesting workers to “delete any naughty emails”.

Meanwhile, AA stores had taken on a different type of toxicity, mostly in hiring and firing practices. “There were no standards of how employees should be treated, or how managers should act,” Sam recalls, “and this behavior went right up the chain to corporate.”

At 19, Sam was hired by a friend who managed a Seattle AA store. A few weeks later he was promoted to floor manager. “I don’t think anyone looked at my resume, I just showed up and was hired. I don’t think most people were actually qualified for the jobs they had.”

Six months in, Sam was upped to visual merchandiser. “To this day I don’t know if I did everything a visual merchandiser is supposed to do, ” he admits. “I placed orders, arranged the store and made sure I enforced the dress code,” which was to wear American Apparel, head to toe. “That meant if someone broke the dress code, the choice was to buy something on the spot or go home.

“We were required to keep the store open an hour past close if we were within $100 of our sales goal. Once I couldn’t stay late, and the next week I saw my hours were cut from 32 to 4. I followed up with my manager and then the district manager, but I was just put in a circle of them referring back to one another. No one would give me a straight answer.”

In 2010, Gawker published a series of anonymous AA employee recountings, which let readers into the catty chaos behind the Helvetica storefronts. For example:

And there were specific conditions on hiring black women:

“It’s an extremely fine line for apparel companies, between articulating brand image and discriminatory hiring practices,” says Smartrecruiters’ Sarah Wilson. “American Apparel isn’t alone in that. It’s a broad challenge in the fashion industry.”

The company will undoubtedly seek out new employees who know and love the brand’s aesthetic, but in the digital space, no one will have to physically embody it: consumer-facing retail positions are generally entry level, whereas UX designers and digital marketers have university degrees or equivalent experience, which both raise the age of entry, and shift focus from appearance to qualifications. “With an e-commerce candidate,” explains Wilson, “it will be less about what you wear to the interview, and more about how you describe the brand’s aesthetic.”

As opposed to the scalability of employee hotness, the label is making a great push to bring its socially conscious side to the forefront, even if it can no longer boast it’s all “Made In America”. With the global relaunch, clothes will be made in both the US and “sweatshop-free” factories in the developing world. Consumers can choose the product source, with the American-made version costing between 17 and 26 percent more.

Without the founder’s nefarious ways to overshadow them, AA’s strides in labor standards could actually garner some good press – including new 24/7 medical clinics for workers in Central America. Charney may have even given American Apparel an unintended boost by taking his bad rep, along with much of the same branding, models, and even former AA employees to LA Apparel.

“I knew Dov,” reflects Sam. “ but I didn’t know about the sexual harassment until it came out in the press. I don’t know what happened, but I err on the side of believing the women, so I couldn’t work for him again.”

And what about American Apparel? What if they asked Sam to come back?

“Nope.”